Citizen science is love.

Founded by technologists with a deep appreciation for the natural world, Tech for Conservation (T4C) is a Vancouver-based organization dedicated to helping conservationists harness advanced technology to protect at-risk animals and ecosystems. African Carnivore Wildbook (ACW) is one of the first platforms they’ve brought to life. We partnered with T4C to evolve and launch ACW — an AI-powered, image-based research platform that enables conservationists to identify, track, and study individual animals using photos submitted by tourists and guides, often referred to as citizen scientists.

Platform Positioning and Brand Storytelling

We developed a platform positioning and brand story that balances scientific rigor with emotional accessibility, emphasizing the connective power of citizen science. The design language and messaging were crafted to resonate with both professional researchers and amateur wildlife enthusiasts — bridging expertise with empathy to invite broader participation without compromising credibility.

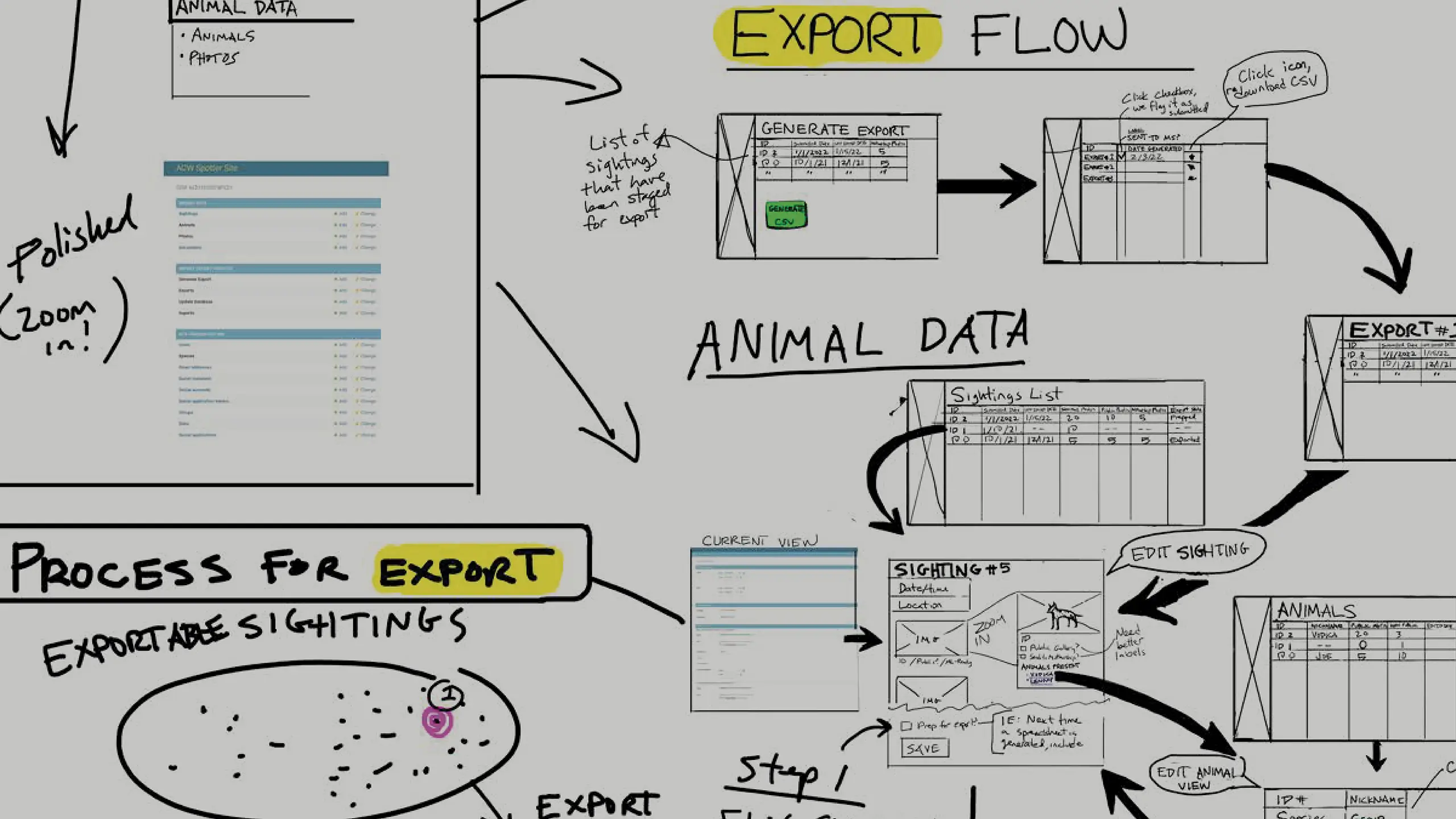

Researcher Interface and Digital Experience

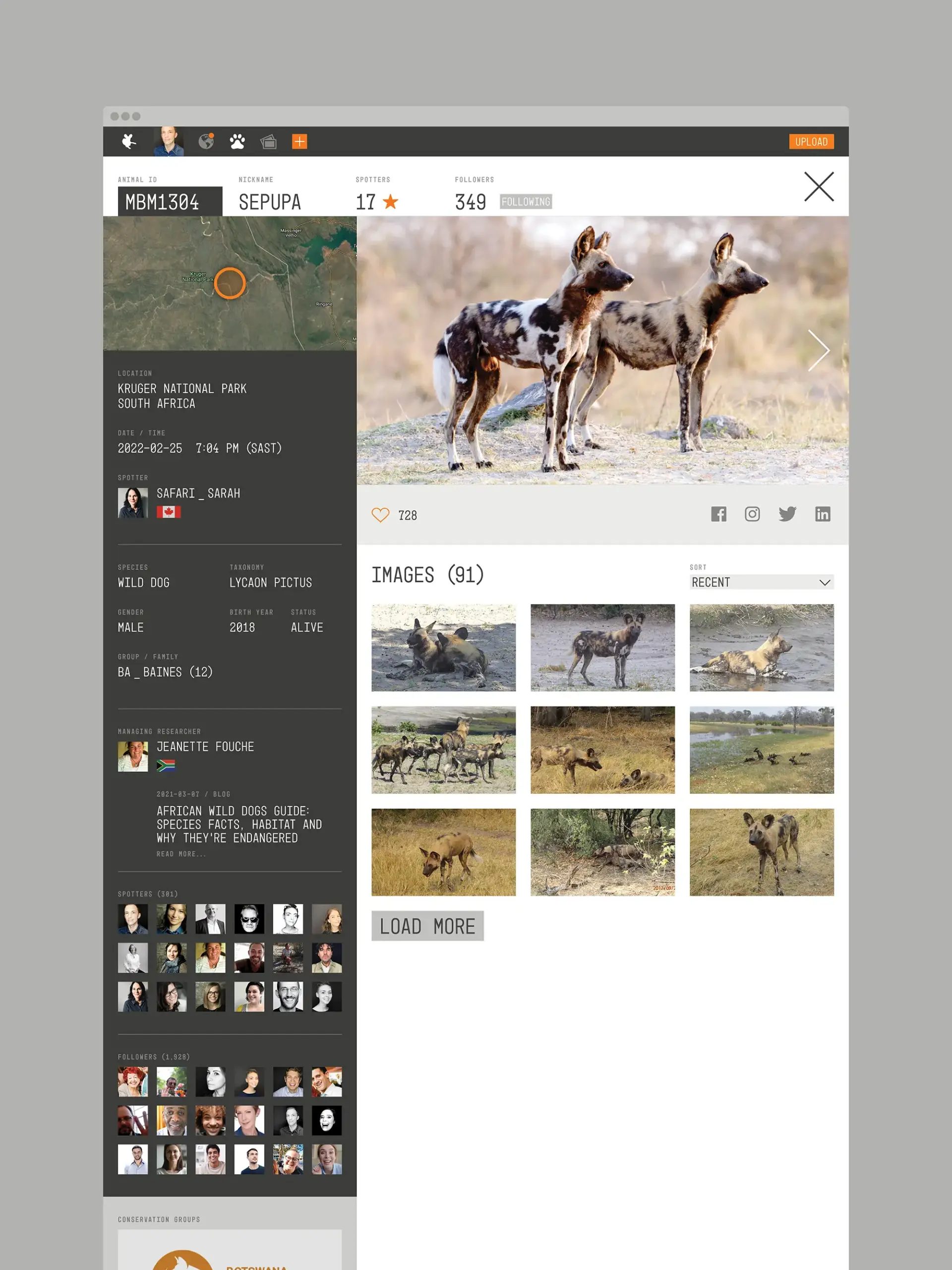

For conservationists, understanding which individual animals were seen, where, when, and alongside which others over time is critical. More data lead to stronger research, deeper insights, and more targeted conservation actions. However, traditional methods — such as camera traps and field scouting — are constrained by limited resources and vast geographic areas, making comprehensive data collection incredibly challenging.

That’s where citizen science becomes transformative.

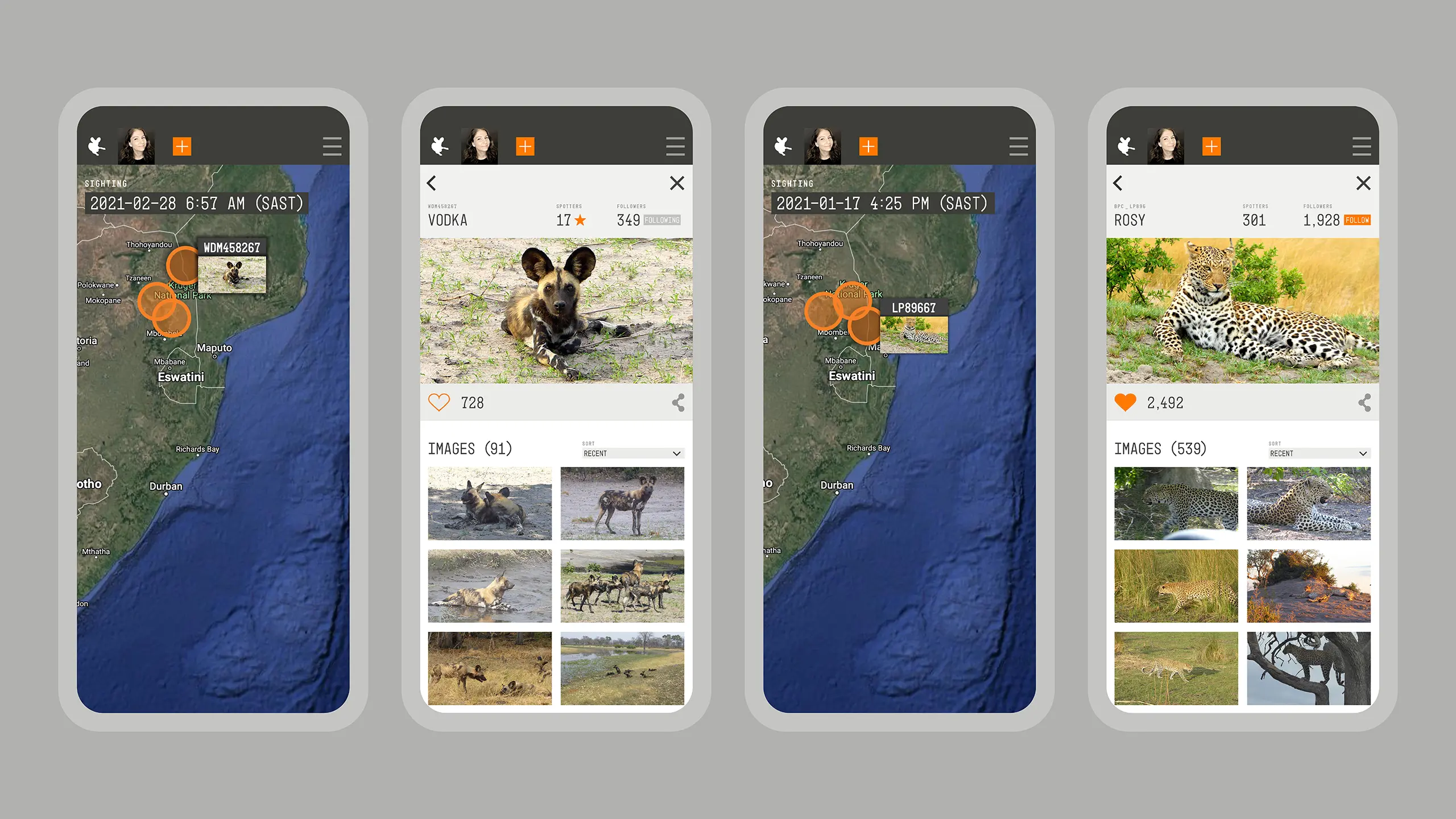

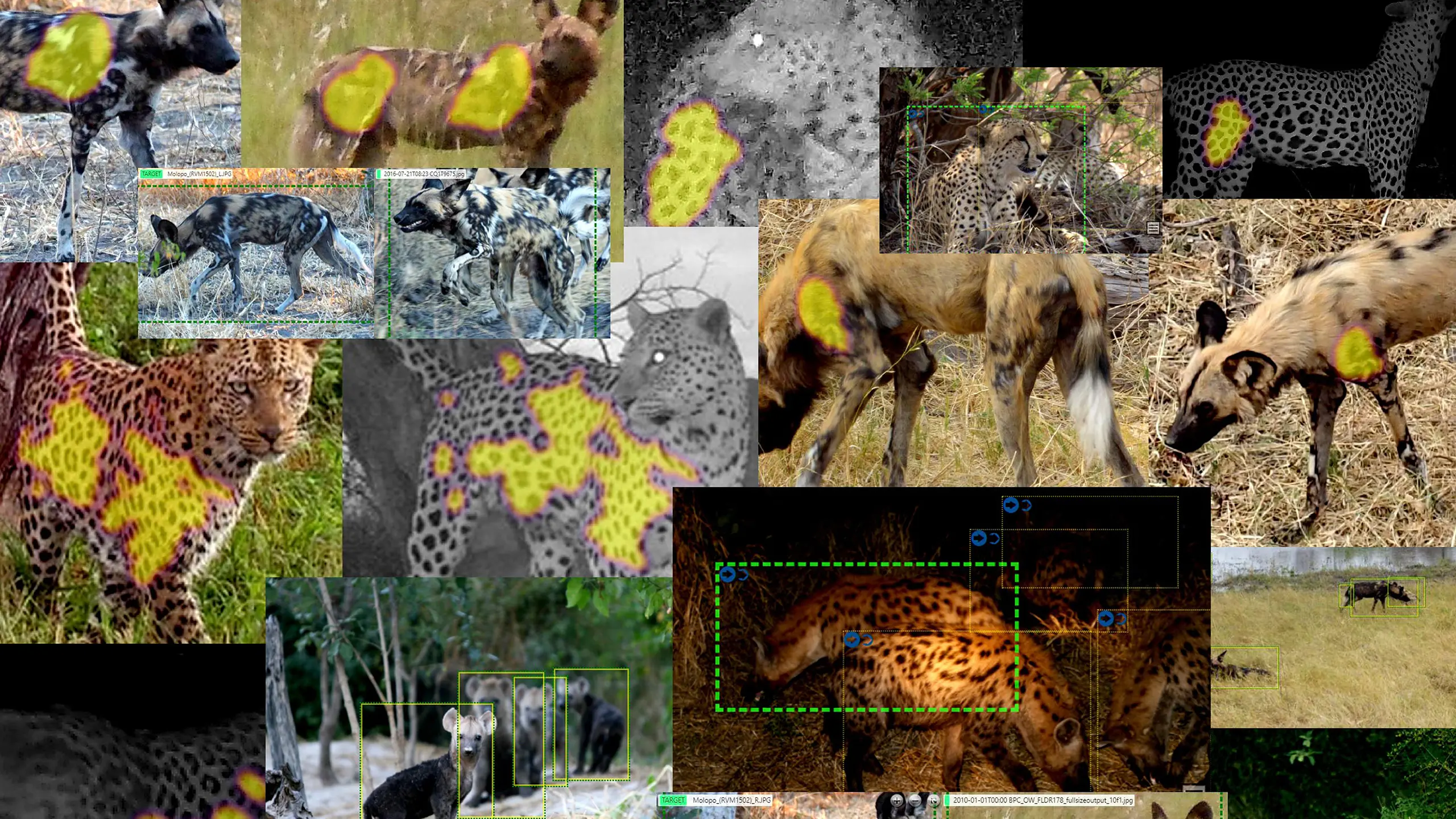

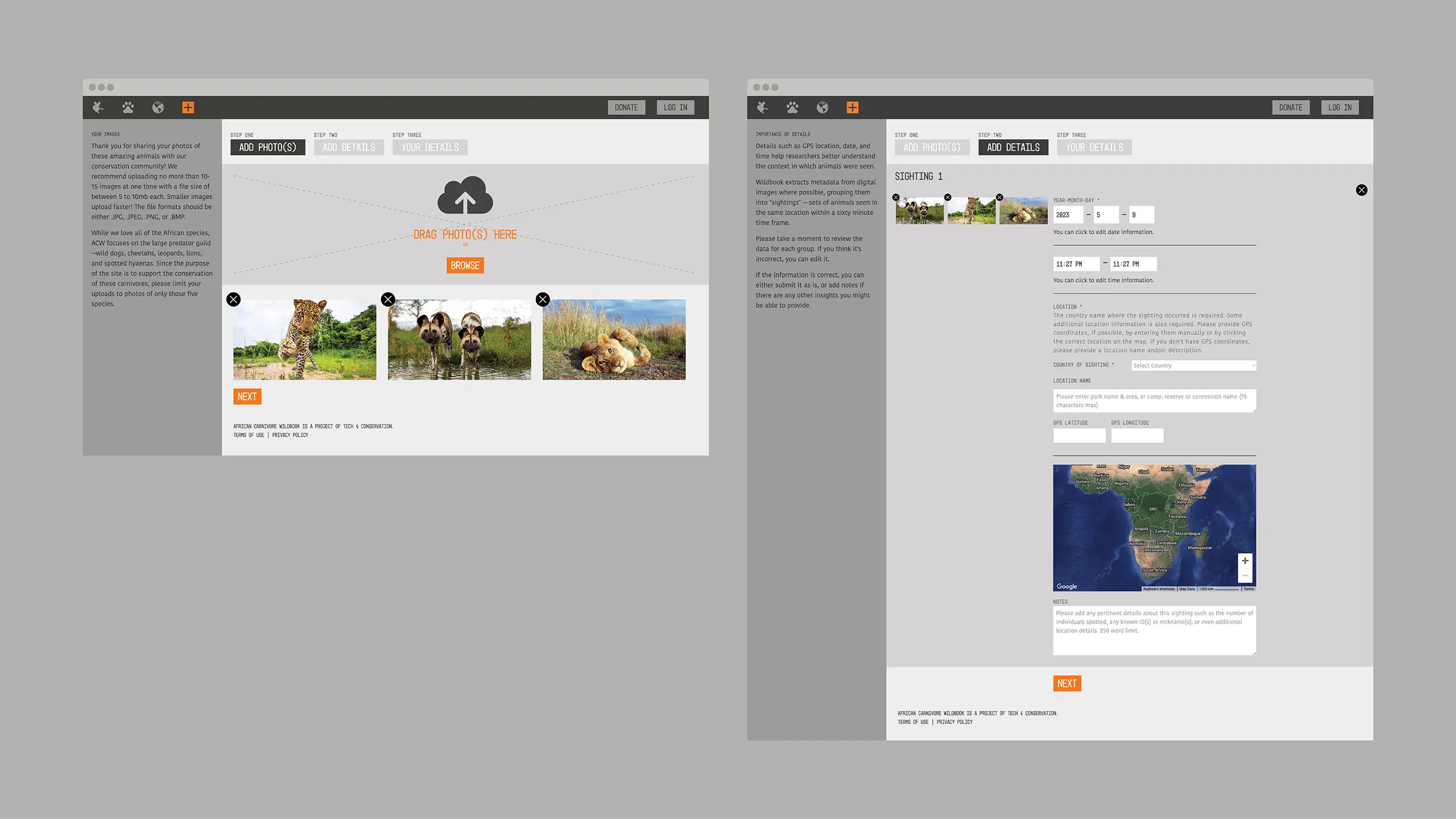

We designed and developed the public-facing research platform that empowers citizen scientists to contribute by uploading personal safari images to the ACW dataset. Through its advanced pattern-recognition technology, these images can then be matched across a large database of researcher images, automating identification and accelerating insight.

The submission experience was streamlined for ease of use across devices while ensuring all essential metadata was captured. To date, more than 1,000 contributors have submitted photos, resulting in the identification of nearly 1,900 individual animals across 11 countries.

Systems Integration

A robust back-end system was designed and developed, integrating the data of citizen scientists and the existing researchers’ AI and machine learning engine database into one seamless, comprehensive experience.

This unlocked rich metadata for researchers, supporting population monitoring, movement tracking, behavioral analysis, lifespan studies, and the study of reproductive trends. Meanwhile, citizen scientists feel a sense of connection to the process, allowing them to follow and learn about the animals they have observed and documented.

Today, 19 conservation organizations use the system to access behavioral and migratory insights that were previously impossible to collect at scale. It’s a powerful model — one that’s already delivering a meaningful and measurable impact for wildlife conservation.

“I think everybody who’s got a love for wildlife deep down wants, in some way, to be a wildlife biologist. This citizen science approach makes perfect sense. We can involve people who are already visiting in the effort and make them an integral part of the research. That gives them a way to contribute and leaves them with a greater sense of belonging, and that’s very important if we want our wildlife and our protected areas to survive.”

Dr. Kelly Anne Marnewick — Department of Nature Conservation, Tshwane University of Technology Pretoria, South Africa