Visualize Change

It’s probably fair to say that most people love life. It’s probably also fair to say that life is change. So you might think it's fair to say that most people love change. Wrong.

It seems that most people hate change, or at least dislike it. A lot. In fact, human beings are pretty much genetically change-averse, conditioned by millions of years of history to favor the known over the unknown. We’ve got the idioms to prove it. ‘Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t.’

Those words of wisdom—passed down through countless generations by well-meaning people whose brother, for example, might have successfully escaped a sabre-tooth tiger attack by running into a cave full of bears—are telling us loud and clear that it’s probably better to stick with a less-than-ideal relationship, product, service, job, whatever than to abandon it and try to find or create something better.

But innovation demands change. Innovation demands examining the known, finding it wanting, and then creating the previously unknown. It demands all kinds of behavior that’s contrary to the basic human instinct to cling to the ‘now’ in case the ‘whatever’s next’ is way, way worse.

On the other hand, when life is truly tough—say, for example, you need to spend 93.45% of your time just trying not to die of starvation, exposure, disease or slaughter by your neighbors—maybe a little innovation is just the ticket? So we’ve also got an idiom or two about that. ‘Necessity is the mother of invention.’

It took us a while to figure out that running after mammoths with pointed sticks wasn’t quite as healthy for us as growing corn and raising cows, but we got there. And of course we were lucky to have the really wild ones—people like DaVinci, Henry the Navigator, Gutenberg and Curie—who not only didn’t listen to their grandparents but also ignored some really scary people for whom the status quo was just fine. Sure, over time we’ve gotten better and better at making change happen, but at heart most of us are still nagged by that whole ‘cave full of bears’ thing. Change is still hard.

Change or be changed.

Today, whether you’re a leader in business, government or education, making change happen is the name of the game. The alternative—having change forced upon you—pretty much sucks, so it’s more important than ever for leaders to find ways to overcome the instinctive resistance people feel when it comes to letting go of what they know and moving toward what they don’t know. Luckily, there’s this:

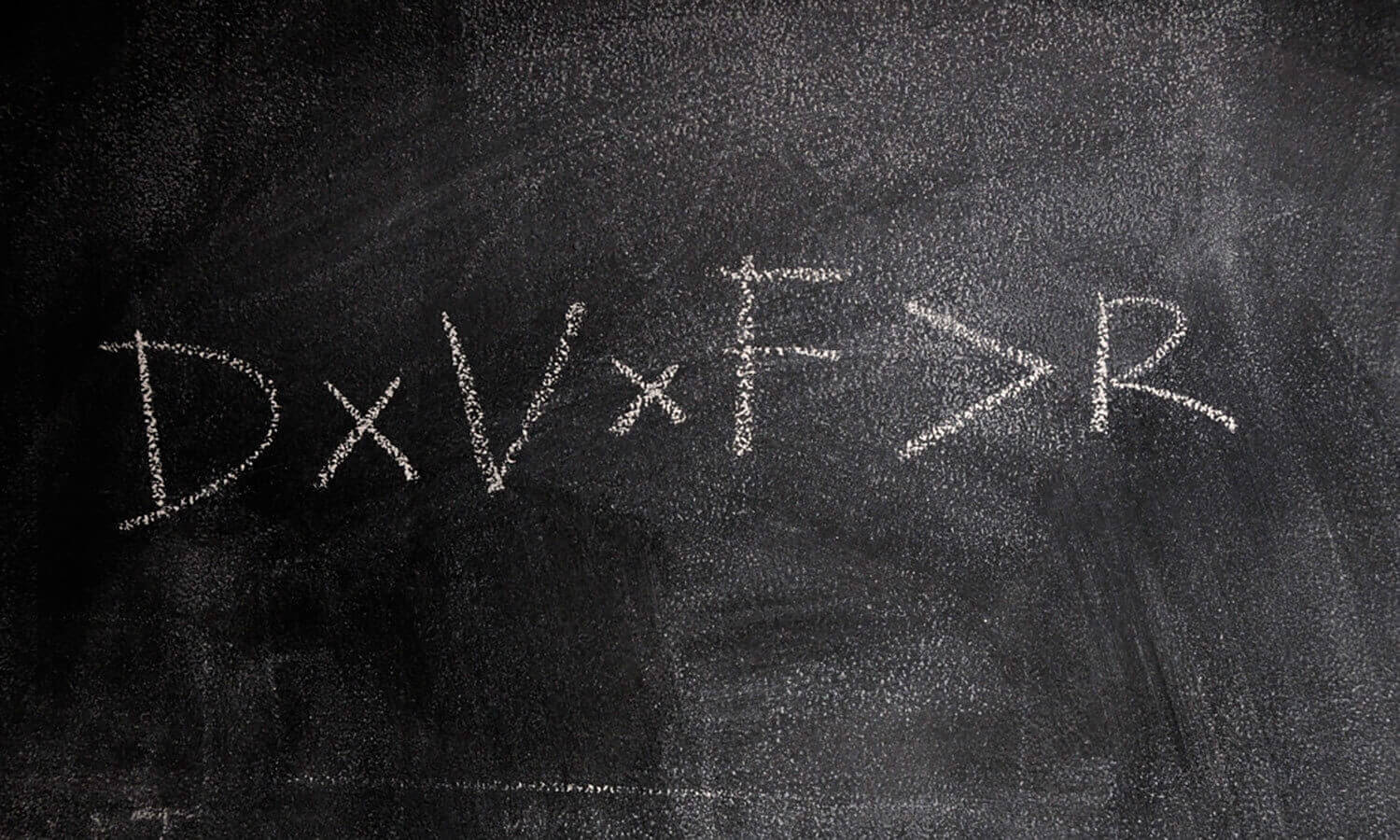

D×V×F>R

The Formula for Change, also known as Gleicher’s Formula, is a succinct way of breaking down the process of organizational change into its key elements.

D = Dissatisfaction with the status quo. Somebody has to be unhappy with the way things are. If that somebody happens to be the CEO or Chancellor or President, that’s helpful. But that somebody can also be a kid trying to buy a concert ticket or a mom in line at a grocery store who sees opportunity in frustration.

V = Vision around what might be possible. Having a vision for a better ________ is what got us from dying old at 30 to dying young at 90. Imagination and the ability to articulate it is bigger than big.

F = First, achievable steps toward change. Big change that happens all at once tends to scare the crap out of people. For example, if you want to get your employees rallied around your vision for a new organization, standing up at the company picnic and yelling out “Hey, everyone! We’re no longer the thing we’ve been for the last 40 years and everything you know and feel comfortable with is vaporizing tomorrow!” might freak some people out. Providing them with a path to change that explains why it's necessary, acknowledges their fears, respects their interests and motivates their positive contributions is the way to go.

R = Resistance to change. People resist change for a lot of reasons. They push back when they don’t understand (or don’t agree with) why change is necessary, feel disenfranchised from the decision-making process or feel change is being forced upon them. They feel threatened when they think that change might negatively impact their established patterns of behavior, working relationships, status or power. And they resist change when the perceived benefits of making it are seen as insufficient relative to the amount of effort it might require. Plus the whole ‘cave full of bears’ thing.

So the formula for change, simple as it may seem, is extremely difficult to enact in real life. Because D, V and F must be multiplied to create one product and one force to act against R, if one or more of those essential elements is not present at all or is present in an insufficient quantity, overcoming R/resistance is likely impossible.

We’re in the change business.

We work with people who have ‘D’. They want to change something about their organizations, products or services because they know in their hearts that those things can be more than they are. And they have ‘V’. They can see potential and can imagine creating new solutions to existing problems. We help articulate 'V' and apply strategic design to provide ‘F’.

The work we do is much more than it seems on the surface. The ‘things’ we create—names, visual identities, videos, websites and communication platforms—are indicators. They’re visible, often tangible or experiential evidence that the transformation an organization is undergoing is intentional and controlled. They represent the first, achievable steps toward bigger changes. The process through which we execute that work—inclusive, engaging, collaborative and consultative—communicates to the people involved that their thoughts and opinions not only count, but can be invaluable in moving change forward, which also helps overcome resistance.

Virtually every organization and everyone wants to change something for the better: a product or service, a reputation, market share, a way of thinking or working, an outlook or a bottom line. Or all of the above. And that includes us.

We’re new partners in a new company. We’ve all got deep and varied backgrounds and we’ve joined forces because we all feel that together we can make good things happen for our clients, our employees and our families. But we’re certainly not immune to the trepidation and angst that comes with making change happen or to the need to positively engage others in that effort. So we’ve practiced our own craft on ourselves, followed our own process and created our own first steps toward the bigger changes we envision. And we’re fired up and ready to go.

Because strategically designing change is way more fun than being unstrategically redesigned by it.