Opinionomics: Brand is a Trailing Indicator

Asshole. Hero. Dork. Superstar. Loser. Cool. Lame. Weird. Awesome. Bogus. Trustworthy. Sketchy. Nice. Awful. Thumbs up. Thumbs down. Like. Unlike.

You've probably heard that because of its importance in their lives, the Inuit have over a hundred words to describe snow. It turns out that claim is an anthropological myth, but its premise—that a culture is likely to develop a large lexicon to communicate about things that are significant to it—has been proven many times over. And the lexicon of opinion is enormous. We're all subject to it, but those of us who work in the world of opinion—business and organization leaders, entrepreneurs, product and service designers and providers, marketers, communicators and image crafters—are constantly working to ensure that the things we care about stay on the right side of the line.

Soft, squishy and all-powerful.

By definition, opinions are beliefs not necessarily supported by facts. And by another, more crude definition, they're like assholes: everybody has one. They're complex and deeply human, and depending on their owners, deemed to be either of little or no value, or of such significant value that they can hold the power over life and death.

In economics, analysis based on observation of facts is referred to as positive analysis: what is. Analysis based on opinion is referred to as normative analysis: what ought to be. Because opinions are a person's ideas or thoughts—a personal assessment, judgement or evaluation of something as opposed to facts—they cannot be proven wrong. But when it comes to business, politics, social structure and countless other things, they determine virtually everything. Opinions perpetuate and change governments, start and end wars, spur and suppress innovation, generate and destroy wealth, oppress people and take them to the stars. So while it may be true that for the most part, individually they don't count for much, collectively opinions decide the fate of the planet.

Economics is for wimps. Opinionomics rules.

Information + opinion = power.

At one time, the majority of opinion was irrelevant. Kings were born, not elected. Conquerors ruled by fear and violence, not by consent. The few opinions that counted belonged to those who could help the powerful keep the powerless exactly where they were. Self-appointed / divine rulers and oppressors held onto power not only by physical force, but also by imposing an information deficit on those they were trying to dominate. Let's face it, if your sources of information were limited to those who held power over you, it's probably more likely that you'd accept the idea that those people knew more than you, and that you really were inferior to them. And if you also happened to believe (ie. were of the opinion) that someone was made ruler by some divine force, well, you'd pretty much be screwed.

It's not necessary to fully understand anything to form an opinion of it, and it's been argued that the less people know about a subject the more likely they are to hold fast to their opinions on it. But informed opinions are a different animal. Throughout history, the so-called elites of the world have worked hard to try to ensure that information—knowledge—that might help create opinions that were contrary to their best interests was accessible only to themselves. But information has a way of making itself available.

The development of symbology, alphabets and written communication revolutionized commerce, learning and society in general, but the development of mass communication tipped the scales against imposed ignorance. Printing presses brought about a paradigm shift in the availability of information and although few people could read the first books, within a few years that capability had become widespread, making the spread of knowledge—which generates informed opinions—extremely difficult to control.

The internet delivered a quantum leap in the number of informed (the exact definition of which is up for discussion) opinions. And because information now flows around the world with almost seamless efficiency, wherever possible, the powerful still try to exert control over it and somehow keep opinionomics in check.

Good girl / bad boy.

It's human nature to look for love, acceptance, affirmation and validation. So it's human nature to care about opinions. We learn early in life that positive opinion generally leads to good things, and that negative opinion typically leads the other way. We learn that, depending on who's issuing it, opinion can be an opportunity or a threat. And we're constantly reminded of its power. We learn that it's foolish to form superficial opinions—”Don't judge a book by its cover.”—and to remember that while we're forming opinions about others, others are forming them about us—”Judge not, lest ye be judged.” The opinions we have about ourselves (self-esteem) are acknowledged as critical aspects of our own well-being.

So we know instinctively that we need to find ways to distribute the kind of information about ourselves that will help others form the kinds of opinions we want them to have of us. We dress and behave a certain way. We smell good or not. We're articulate and polite or not. We're talkative and loud or introverted and quiet. We're trustworthy, loyal and kind. Or not. The aggregate impression we make in the minds of every person we come into contact with is manifested in their opinion of us.

In human terms that aggregate impression is often referred to as reputation.

In the business world it's commonly referred to as brand.

We've got the power (sort of).

The value of a reputation or brand is ultimately determined by a market of opinions. They can consist of a single person or millions of people, but opinion markets determine the price and longevity of goods and services, decide who gets to be in charge, who plays and who rides the bench, who goes to what school or stars in what movie, and ultimately who wins and who loses in the majority of businesses.

A stock exchange is an example of a reasonably efficient opinion market, where the metrics of opinionomics are manifested in financial terms. Every publicly traded company has its own opinion market: an interconnected and interdependent group of individuals—customers, institutional and retail shareholders, regulators, analysts, employees and the media—whose opinions can affect it. But there are opinion markets within opinion markets. The opinions and actions of a publicly traded company's customers form the basis of all other opinions within its larger market. In an open market, buying one product or service instead of another is an expression of opinion. If enough people decide that a company's products or services are worthy of a positive opinion and are willing to pay for them, the company's bottom line may grow, and its enterprise value (also known as its multiple!) may increase in direct proportion to the more positive opinions of other members of the market.

Opinionomics can also drive stock prices higher in spite of annoying realities such as a company having no earnings or real prospects for long-term profitability (remember the dotcom bubble?). And vice versa. If the opinions of enough customers, regulators or shareholders prove to be negative, the opinions of other members of the market may be inclined to follow, affecting everything from sales to stock price to the the employment horizon for its executives and the viability of the company itself.

As the saying goes, the market is never wrong. Unless the market is wrong. In theory, democracy relies on the premise of opinion markets: equal value in the expressed opinions of individuals to determine the outcome of elections. But in practice, pure democracy is rare. Many democracies, including the U.S., have mechanisms such as the Electoral College in place to ensure that the full power of opinion is not actually unleashed. Because the Electoral College is a manipulated (some say rigged) opinion market, its outcomes can be 'wrong,' leading not only to the election of leaders who do not benefit from the positive opinions of the majority but also to the emergence of a significant percentage of the population whose opinions of democracy itself are so low that they choose not to participate in it.

I don't care too much for money, money can't buy me love.

But we do care for love, because love buys money.

The corporate world has institutionalized the business of trying to cultivate positive opinion. Advertising, public relations, investor relations, social media and SEO are conscious attempts to consistently produce and disseminate the type of information that will generate positive impressions in the people whose opinions are valued the most—the members of a corporation's opinion market. 'Love' would be fantastic, but 'like' will do fine for the most part. Of course, as opinion markets become more informed they're becoming harder than ever to influence.

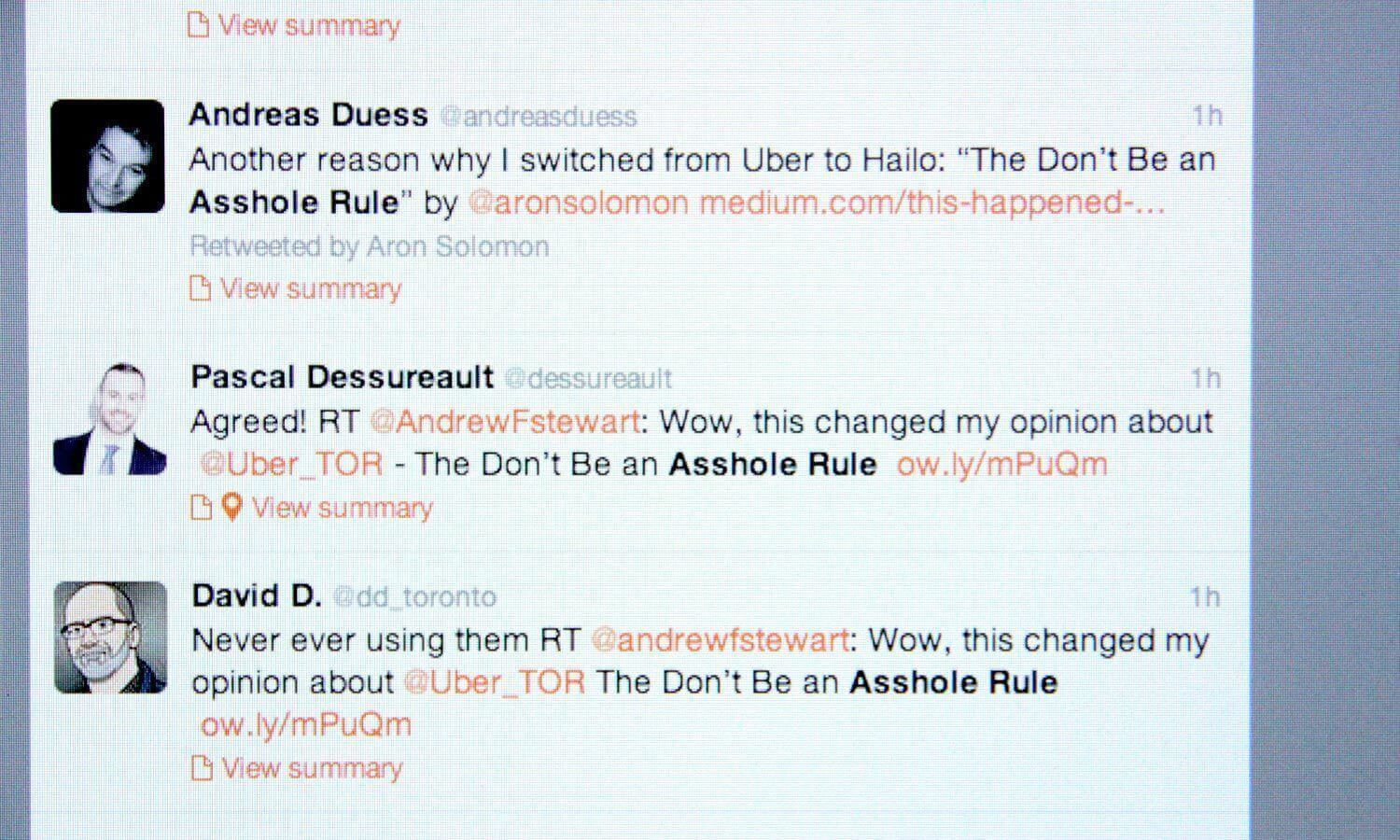

In an environment where data can be gathered from a massive number of sources, the power of one individual or entity to influence the opinions of others is diminished. Opinion is now shaped by access to huge amounts of information and virtually instant exposure to the opinions of others (ask Uber what happened when blogger Aron Solomon called them out for their pricing policies during a recent heavy rain storm in Toronto). That complicated reality has marketers and advertisers desperately trying to find ways to get the information they can actually control—the messages they want their opinion markets to buy into—through the filters, barriers and competing information sources that might get in the way.

Opinionomics drives the boat. Can you waterski?

So what does all of this mean for people who are in the business of attempting to cultivate the positive perceptions of others? In an interconnected, mobile and hyper-informed world, old school push communication models like telling people you're awesome through advertising don't really cut it. On the other hand, owning a great brand rocks. Because brand is a trailing indicator, working hard to be really good at the things that generate it—literally every aspect of an organization's being, from its products or services to its employee / customer interaction to its corporate citizenship and top to bottom communication—turns out to be a pretty effective positioning strategy. And pretty profitable.

Basically, if you're not doing everything you can to put your best self out there 100% of the time, if you're not being the absolute best at whatever it is you do, offering fair value and a consistently positive experience, and if you're not communicating clearly, honestly, authentically and strategically with the people who matter the most to you, you're probably not going to matter much to them.

And that means opinionomics is going to get you.